7.13.2006

talking to a conservative

Reminds me of the time I saw a woven wallhanging in the home of a particularly well-to-do right-wing person I know. It was made in Pakistan and had the artist's signature on it, and I said I was glad to see that because it meant that it was unlikely to have been made by slave labor. The person's response? "Well at least they [enslaved children] get food, water, and a place to sleep." Apparently, sometimes even decrying slavery is too liberal.

7.09.2006

Lisa Schwarzbaum: Stop Annoying Me!

In particular, I have long found myself in disagreement with her when it comes to animated films, where it seems she’ll praise anything CGI over anything handdrawn and glorify Pixar in the highest. Her panning of Lilo and Stitch focused on its drab drawings and trite plot, while I found its broad notion of family progressive and its attempt at a Hawaiian aesthetic charming if superficial. By contrast, she adored The Incredibles, finding both content and style original, glorious, magnificent. Never mind the glaring patriarchal, white, middle-class nuclear family-ness of it all.

Now I’m confronted with her reviews of two new Disney flicks, Cars and Pirates of the Caribbean II, and I’ll be damned if I can make the slightest bit of rational sense out of what drives her opinion, yet again. She labels Cars a “beguiling comedy adventure,” while Pirates II is merely “ostentatious extravagance,” an interminable theme-park ride, “a hellish contraption into which a ticket holder is strapped, overstimulated but unsatisfied, and unable to disengage until the operator releases the restraining harness.” Funny, my experience of the two films is pretty much the opposite, though I wouldn’t go to such extremes, and I could easily reverse her descriptions and find them apt. To me, Cars’ main characters were simply “whirling teacup figurines” rather than (or perhaps as well as) Will and Elizabeth of Pirates, and the focus on car racing (especially the races themselves) made me feel strapped in, “overstimulated but unsatisfied.” In fact, even my seven-year-old son was bored with Cars and more than ready to leave and forget his experiences (except the tractor-tipping, which he found troubling to his animal-rights loving spirit, though he has not quite been able to articulate why because they were tractors not cows, or were they?).

Honestly, I didn’t loathe Cars and I didn’t find Pirates II an unqualified piece of cinematic brilliance. Both were superficial flights of fancy, both were Disnified escapism. Cars did attempt to offer a message about how fast we speed past the “beauty” of little towns and out-of-the-way spaces because we’re always on interstates going 80 mph, but in the face of our guzzling imperialistic oil-dependence as a nation, I found the message nostalgic and trite. I much prefer the corporate critique of Monsters, Inc., if we’re championing Pixar.

And good heavens, Lisa Schwarzbaum does love her some Pixar. She gushes, “I [...] bet that any story the Pixarites came up with about dust and socks [...] is bound to be more rewarding than 90 percent of anything coming out of Hollywood Blockbusterville this summer.” While I’ll grant you that “Hollywood Blockbusterville” generally does suck (for artistic and political reasons Schwarzbaum is only occasionally willing and able to engage), glorifying Cars because it features a “bunch of computer-animated, anthropomorphized vehicles who express emotion with eyes made from windshields and smiles from metallic front grills” then slamming Pirates because it features human-portrayed characters without greater depth is to fail entirely to understand that making a CGI car come to life is a hell of a lot easier than turning a human being into an effective cartoon, as Depp does so joyously and with such fabulous effect with his Captain Jack Sparrow.

Moreover, to champion Cars by giving it an A- and to bash Pirates II with a D+ on the basis of plot is beyond inane. Cars offers a time-worn tale, the upstart who has to learn his lesson the hard way (“The Tortoise and the Hare” meets “City Mouse and Country Mouse”). I have no problem with this emphasis nor the choice of cars/racing as a focus. But let’s call it like it is: a film for NASCAR fans and Southerners. If you don’t like racing and you don’t like Blue Collar TV, you may find yourself more than a tad bored with the film’s trajectory. Now I’m the first to admit that Larry the Cable Guy provided fabulous white trash humor in the film; and it may be the fact that I’ve been living in middle Tennessee for 15 years that let me laugh with his bubba truck character, Mater. But, really, even George Carlin, Click and Clack, and Cheech Marin couldn’t keep me from yawning as the predictable plot unfolded.

Pirates II ain’t Shakespeare, but if the plot truly was “barely intelligible” to Ms. Schwarzbaum, then I don’t know whether she was simply not paying attention or is looking for random excuses to hate the film. I was delighted with the twists and turns and never bored. Perhaps Lisa was not allowed to play pirates as a kid or they always made her swab the deck.

Finally, to blast Pirates II because its ending makes plain there’ll be a Pirates III but fail to note that Cars has spawned a billion-dollar merchandising extravaganza before the film was even released (and I’d guess there will more than likely be a TV show on the Disney channel by 2007) is to be blind, ignorant, or just incapable of a good film review. You be the judge.

Superman Returns, and I Go See Him!

After a fabulous evening of escapism to see Pirates of the Caribbean II on its opening night in Bradford, Pennsylvania with my mother and her husband, we decided to risk deflation by going to see Superman Returns the following night. I did not expect to enjoy the film much, not being a fan of the Christopher Reeve’s films and not particularly liking this particular superhero overmuch, finding him too stiff, too patriotic, too uptight. I generally prefer more complex, angst-ridden superheroes, from X-Men to Xena. So I was much surprised by what I found in this new Superman.

First, I was quite pleasantly surprised by Brandon Routh’s easy, comfortable portrayal. I liked his quiet voice; I relaxed into his small gestures and controlled, compelling facial expressions; I enjoyed his combination of confidence and insecurity. And I grooved on the silent and smooth way Superman flew. With a risk of falling prey to reactionary white masculinity in superheroic form, I found a real allure in his mellowness. Unlike the excessive X-Men, I did not feel overwhelmed by constant slashing and crashing. Unlike the twitchy adolescent Spiderman, I was not nervous watching him. Unlike the dark Batman of recent memory, I did not have to worry that he would act unpredictably, jarring my senses every scene.

What was best of all for me in the film was the way it challenged conservatism that I entirely expected to see. I’m not arguing the film is radical. But, I like that the film makes Lois a single mom with mediocre parenting skills to say the least. She forgets to pick her son up, takes him to follow up a lead that takes her right into Lex Luther’s lair, and doesn’t worry overmuch that he might be traumatized for life by what he has been through. I also really like that the limits of the nuclear family are pushed in the film. Lois’s fiancé Richard keeps his machismo at bay, doing a lot of the parenting (and better than mom) and letting Lois call the shots in their relationship, from waiting around until she is ready for marriage to going back to save Superman at her command despite his jealousy and fear that he may lose his already skittish fiancée to him. While the film could use this depiction to make the character dismissible, a placeholder until Superman can come along and sweep her off her feet again, it does not. As we see in Jason’s drawing of the family, Superman, Richard, Lois, and Jason can all be a family together. Ok, we don’t get true polyamory (Lois and Superman do not even kiss in the film), but we do get a sense of alternatives that do not require traditional marriage as an endpoint.

This is capped off with a resistance to gratuitous nationalism and flagwaving—as Superman lets us know that he hears the voices of the suffering all over the globe and not just in the God-blessed U.S. of A. This is highlighted when Perry White—played with love by Frank Langella—actively resists completion of the Superman tagline “Truth, Justice, and the American Way,” reflecting that truth and justice are the real concerns here and the “American Way” is outdated, predictable, perhaps irrelevant, and maybe even distasteful in today’s global economy.

Such delights let me ignore the poor casting for Lois, the glaring plot gap of no one noticing Clark Kent is missing for the entire time that Superman is in the hospital, and troubling awareness of ongoing American desire for escapism in superhero discourse (however cynical it usually is) rather than waking up and changing the way we live our lives and practice our version of democracy. With chin clefts and ultra-blue contacts like Routh’s, it’s so tempting to feel reassured when Superman says, “I’m always around.”

6.28.2006

Two Quotations

"Artaud believed that the function of theatre was to teach us that 'the sky can still fall on our heads.' [...T]he Slapstick Tragedy that opened on September 11th was also a theatre of cruelty and might warrant some utopian explorations. The sky has fallen on our heads, and what we are seeing [...] threatens to blind us. At a time when every cultural practice is reassessing itself and its role, perhaps we will entertain Artaud's mad vision of theatre as a place to encounter the unknown and the unimaginable, a place that teaches us the necessary humility of not knowing."—Una Chaudhuri

6.10.2006

Deadwood, Queerness, and Domesticity: Can't Stop Watching It!

The Western has long been an important genre through which repressed homosexuality thrives. As Brokeback Mountain acknowledges and the montage Jon Stewart unveiled at the 2005 Academy Awards outs, getting a bunch of tough, emotionally challenged men together is bound to result in some hanky panky, however codified.

In more sophisticated terms, Steve Neale, in “Masculinity as Spectacle” (Screen 24.6, 1983, pp. 2-16), argues that “‘male’ genres” of film are “founded upon a repressed homosexual voyeurism.” He notes that “in a heterosexual and patriarchal society the male body cannot be marked explicitly as the erotic object of another male look: that look must be motivated in some other way, its erotic component repressed.” (Note: I also use Neale’s focus to discuss the voyeurism and masculine anxiety in Fight Club: here.) In the Western in particular, there is significant focus on intense rivalries between (two) men, fetishization of phallic weaponry, and what I would call “intimate” violence (two men slugging each other and rolling around in the dirt). Neale discusses how such elements encourage male spectators to adopt an erotic gaze usually reserved for viewing female characters. Though they are not passive, as in the prototypical Hollywood female sex object, the activity of men in Westerns is stylized to be watched, and the line between violent display and sexual display is often thin.

While Brokeback Mountain uses this insight in its overt depictions of homosexual intimacy as a sometimes-violent, emotionally complex and difficult subject, particularly for its homophobic protagonist Ennis Del Mar, Deadwood offers repressed representation, the series being deeply invested in reinvigorating the Hollywood Western tradition. Arguably a “meta-Western,” commenting on the genre primarily through depictions of omnipresent muck, glorification of foul language of a sexual nature (especially “fuck” and “cocksucker” and “cunt”), depictions of women-as-chattel, and unremitting graphic violence, the series does not opt to comment on other generic elements, such as the predominance of whites and heteronormativity. Racism against Asians and Native Americans/Indians we do see, but Indian characters and such commonplace realities of the Old West as African American cowboys and prospectors are nigh invisible (in the first season and into the second at least). And repressed homosexuality abounds through the miasma of machismo the series exudes.

I’m not sure whether the gay overtones in the relationship between Al Swearengen and Seth Bullock are intentional or not. It is possible that the writers are aware of the homoeroticism of the Western and are enjoying it, particularly in the heavy-handed swagger of hyperhetero Bullock. But, in the first episode of the second season, when Swearengen calls Bullock out for his dalliance with the widow Alma Garret and the two end up stripping (ok, Bullock just takes off his gun and badge) and wrestling and punching until they fall off the balcony and land in the mud, one atop the other, exhausted—well, it’s just too queer to miss. (Punching in male genre texts always has violent sexual overtones, as I read it, but the tumbling tumbleweeds way these two roll around just made me laugh out loud. Just admit you want to fuck him, Al, and get it over with.)

I also see homoeroticism in Sol Star’s sidekick hero worship of Bullock, but it’s nowhere near as fun(ny) to watch as Bullock and Swearengen.

There is also a fear of femininity that is part of the repressed homoeroticism of Deadwood. As I read the movement from first to second season, as Deadwood goes from camp to government-controlled county, there is an encroachment of domesticity, represented literally by women who exemplify the figurative invasion of femininity. Steve Neale’s analysis of the Western also includes discussion of gendered codes whereby the male hero must reject literal and figurative domesticity (no marriage or children for the sheriff/marshal, a rugged individualism and need for open spaces). Hence, women represent a threat to Western genre masculinity and must be contained (as hookers, or butch drunks like Deadwood’s Calamity Jane) or gotten rid of (consider Joanie’s threat to Cy Tolliver as she develops a need for independence). (This is also the mechanism of the male gaze, according to Laura Mulvey.)

Yet the encroachment of femininity reaches beyond literal female characters to a more generalized anxiety/fear of the domesticity that femininity signifies in the genre. Swearengen’s fear of losing power and control over Deadwood is significantly greater when he faces the domesticating government than entrepreneur Cy Tolliver; Bullock is far more threatened by the arrival of his wife and child than any other dangers in Deadwood; and even Calamity Jane can only shout “cocksuckers!” at the stagecoach that brings new whores (to be managed by a Madam and not a man) as well as Bullock’s wife to town.

Interestingly, the character most impacted by this change in town is Alma Garret. She has spent much of her time in Deadwood first drugged by laudanum then peering out of her window, gazing at this masculine space and wanting to be part of it; yet being told, repeatedly, that his is not her place. First, her husband keeps her cloistered (hence her escape via drugs). She does not love him, but more importantly, he also symbolizes her entrapment by gendered norms. When he is killed, she experiences a desire to live beyond upper-class feminine norms, and begins to do so. Though saddled with a child—a heavy domestic dose—prostitute Trixie provides the opportunity to shed this sudden maternal role (an option generally available to upper-class women) but also to see beyond other traditional feminine behavioral norms for women of privileged class. Alma wishes to venture forth into this non-domesticated world. At first, she uses Wild Bill Hickok then Seth Bullock as her “agents,” living vicariously through their freedom (something Calamity Jane is also permitted through her dress and crass manner—though she has her feminine vulnerabilities). But as she decides to stay in town she is asserting a feminist resistance to gender norms. She is still too mired in gender and class norms to do everything herself, so Bullock serves to rid her of a conman father who uses her femininity against her to attain his greedy ends and to give her access to sexual pleasures beyond the marriage bed.

My main point here about Alma, however, is how domesticity returns from without to threaten her budding independence. Through the symbolic arrival of Bullock’s wife and child, Alma is staggered by the changes coming to Deadwood. The domesticization of the town does not threaten her as overtly as it does Swearengen and Bullock, but approach of civilizing influences in which she may be expected to return to her “proper” feminine role are definitely a key tension as season two begins.

Though I am still routing for a more developed and satisfying role for genderbender Calamity Jane, as I watch the second season on DVD, Alma appears to be the most dynamic and gender complex character in the series. Well, unless Al keeps getting queerer.

6.06.2006

Doctor Who: Bi TV

The new incarnation of Doctor Who (first season just now airing in the States) does a superb job of retaining the old “feel” while adding some new flourishes—

primarily in the areas of character development and relationships. First, the Doctor tells us that the entire Timelord “race” has been wiped out. So now he’s even more of a loner and renegade. Second, he’s flirty.

primarily in the areas of character development and relationships. First, the Doctor tells us that the entire Timelord “race” has been wiped out. So now he’s even more of a loner and renegade. Second, he’s flirty.It’s delightful to see the very charismatic Christopher Eccleston play the Doctor with such working-class-boy-made-good chutzpah, excited like a child when he saves lives instead of destroying them (a great comment on the death toll of many a past Doctor’s life) and impishly flirtatious with his assistant Rose, the sweet blonde who’s even more white trashy than her predecessor Ace, and other young women he meets.

At the moment, though, I most want to praise the new Doctor Who for the

character of Captain Jack Harkness. Reminding me a lot of an even flashier “Ace Rimmer” (Chris Barrie’s alter-ego from the British SF sitcom Red Dwarf), John Barrowman (whom I know best as a singer—his work in the Sondheim revue Putting It Together and part as Cole Porter’s lover in De-Lovely come to mind) is wonderfully hyper-competent and out-flirts the Doctor repeatedly (much to the Doctor’s dismay). Best of all, in the first season, he’s entirely and openly bisexual in his attractions, flirting with equal pleasure with women and men. I particularly loved the moment when he created a helpful diversion by chatting up a group of WWII pilots. Even when the Doctor finds Captain Jack an annoying nuisance (with obvious streaks of jealousy of his attractiveness to Rose and everyone else he meets), he never shows distaste for his omnivorous sexual attractions. I find this a delightful way to depict a future where bisexuality can be taken for granted.

character of Captain Jack Harkness. Reminding me a lot of an even flashier “Ace Rimmer” (Chris Barrie’s alter-ego from the British SF sitcom Red Dwarf), John Barrowman (whom I know best as a singer—his work in the Sondheim revue Putting It Together and part as Cole Porter’s lover in De-Lovely come to mind) is wonderfully hyper-competent and out-flirts the Doctor repeatedly (much to the Doctor’s dismay). Best of all, in the first season, he’s entirely and openly bisexual in his attractions, flirting with equal pleasure with women and men. I particularly loved the moment when he created a helpful diversion by chatting up a group of WWII pilots. Even when the Doctor finds Captain Jack an annoying nuisance (with obvious streaks of jealousy of his attractiveness to Rose and everyone else he meets), he never shows distaste for his omnivorous sexual attractions. I find this a delightful way to depict a future where bisexuality can be taken for granted.Can’t wait for season two to air!*

*Yes, I know Captain Jack is getting his own show in England as I type... I'm guessing it won't make it to US television (or beyond a first season)--he's not the lead character type, imo, but let me know if anyone out there sees it.

6.02.2006

Child Porn and Octavia Butler's Fledgling

Butler’s protagonist, the amnesiac Renee/Shori, looks 11 but is actually 53 (still a child in vampire—or, as they call themselves, Ina—years). I won’t go into too many plot details, but suffice it to say she gets involved with Wright, a 23-year-old human male (i.e. bites and unintentionally compels to become her companion). They begin what Butler calls a symbiotic relationship. This is a central core to all of Butler’s fiction, and I cannot help but think about it alongside my knowledge of the author’s relatively solitary life. Her fiction often suggests that it takes outside forces to bring people together and keep them together. When not dealing with outright enslavement, the most intense relationships in much of her writing are about beings compelled to stay together. Often it is alien chemistry that does so or an absence of other viable options. Rarely do two characters meet, fall in love, and stay together.

Now, in Fledgling, Butler pushes an interesting envelope with her symbiosis theme, as she has this pre-pubescent-seeming vampire gal have sex with Wright. She enjoys giving him pleasure through her bites—and the particularly sensuous licking of his neck—but also through sex. Wright definitely expresses concern that he’s being seduced by a flat-chested, pubic-hairless girl, but he absolutely takes the elfin "child" into his arms and does the deed. Butler makes sure to make our heroine the aggressor, to show Wright’s discomfort, and even to make jokes about it. The word “jailbait” is used (an understatement!); and, when Renee/Shori meets another of her kind (so far he says he’s her father), he taunts Wright with reference to how others might see his relationship with this apparent pre-teen.

The first sex scene between them is, so far, the only one described at all, and Butler is, as always in her fiction, hesitant to describe sex graphically. (I repeatedly feel she simply does not understand love or lust; like Orson Scott Card, I get the feeling that passion escapes her entirely or turns her off.) But choosing to depict sex between consenting people who are not both adults is a risky proposition and I have mixed feelings about it. In choosing a protagonist who appears so young and also has amnesia, is Butler offering commentary on our current obsession with stopping child porn? (I read the current administration as using child porn concerns to further its McCarthy-esque invasions of privacy, but let’s leave that lie for now.) Is Butler pushing boundaries, intentionally depicting something that makes readers uncomfortable in order to challenge a current trend to censor rather than analyze? Is she commenting on the Christian Right’s hungry brush that tars a wide path of everything it deems “obscene” or “immoral”? Or is she, less politically but very typically for Butler, just messing with our easy reliance on rigid, overly simplistic categories (adult/child, moral/immoral, human/other)?

In any case, the opening of the novel did make me uncomfortable, and I’m sure intentionally so. Furthermore, however, it also made me angry. Following the Lenny Bruce quotation I cited earlier in this blog, I am frustrated by what we deem smut and what we deem “literature” and who can get away with what and how. If it’s “literature,” then you can describe an 11-year-old female body writhing on top of a 23-year-old male one. Yes, Butler must quickly explain that she’s not really 11 and she’s not even human, but she still has this guy fuck a kid before our startled eyes. (My husband is reading the novel Aztec right now and comments that it, too, contains sex with children, in this case because it is relying on historical evidence that the Aztecs did this.)

By contrast, if Fledgling or Aztec emphasized sex as central to the novel and was brought to a publisher of erotica, it would never have made it to print. There'd be no passing the huge “NO UNDERAGE SEX” warning. They also have NO BESTIALITY, NO RAPE, and other prohibitions, upholding these to stay in business in a difficult cultural environment, like those porn sites that now have to keep consent forms for every nude photo they post.

This reminds me of another literary/porn anecdote: about 10-15 years ago, a publisher issued a reprint of Samuel Delany’s pornographic novel Equinox. At the time, I found it excessive and in no way arousing, full of sex with minors, questionable consent issues, and very unsavory (unwashed) characters. (And now I can’t find my copy to see how I'd read it today.) What I remember most is an editor’s note that preceded the text, stating that the ages of every character had been increased by 100 to address concerns with child porn and consent! So the kids were now 110, the adults 142, etc. It was simply absurd, but also an interesting way to address the issue of censorship. We couldn’t publish the book as written (and originally published in 1968), so we had to do this stupid thing and pretend they’re all longlived aliens!

In the end, I’m not sure whether Butler—who always depicts lovers with big age differences where the woman is much younger than the man (Lauren was 17 to Bankola’s 45 in Parable of the Sower, if memory serves)—is making political/social commentary, trying to make readers uncomfortable as a psychological strategy, or just exploring the nooks and crannies of her own psyche. However, as always, she does make me think. Not a bad contribution to human existence, especially in this day and age.

5.25.2006

Making Peace with the Guilt Monster

My wise graduate school buddy Jan once said, “Guilt is never a good reason to do anything.” I do agree with this sentiment, though I long ago lost count of the wide variety of things I have done and the countless times I have done them out of guilt. I joke that it is inherent in the Jewish experience (and the Catholic, Baptist, and, well, pretty much all of the Judeo-Christian tradition—which explains my friends who’ve become Pagans as well as those who’ve become atheists perhaps better than just about anything else I can think of), but it does burden me.

My wise graduate school buddy Jan once said, “Guilt is never a good reason to do anything.” I do agree with this sentiment, though I long ago lost count of the wide variety of things I have done and the countless times I have done them out of guilt. I joke that it is inherent in the Jewish experience (and the Catholic, Baptist, and, well, pretty much all of the Judeo-Christian tradition—which explains my friends who’ve become Pagans as well as those who’ve become atheists perhaps better than just about anything else I can think of), but it does burden me.Now, I’m better than I used to be, working harder to distinguish purely guilt-induced motive from guilt-plus, where there is some other reason I might do something as well as a little guilt engine driving it. Compromise, the Golden Mean. I still haven’t gotten to the anti-guilt state my friend Rick touts, embodied in his slogan “Always take more than your fair share of the available resources.” Even though he is careful to point out the qualifier “available” here, it just smacks of more greed than I can usually muster. (But then, I’ve seen Rick, too, knuckle under to guilt, that Great Equalizer—we all do.)

This topic came up for me this morning in particular as I watched my son amble off from my car to his first-grade classroom. Chewing his hair a bit, walking with a casual, weaving gait, he was making his way casually and calmly. I caught myself thinking, as I have thought before, how he has his own little life that I am not part of. And how that is FINE. I want him to have a life of his own. For one, it takes some responsibility off me for what his moment-by-moment existence consists of. This is not to say I like our educational system, Bush’s inane and evil “No Child Left Behind” test-mania plan, our particular grammar school, or my son’s particular teacher. But I like knowing my child has some responsibility for himself as he makes choices of friends, playthings, how to color his worksheet, when to ask for a drink of water, and what in his lunch to eat and what to mash into a little ball in the bottom of his lunchbox for me to clean out. And I like this, at least in part, because it frees me of responsibility (a.k.a. guilt) for a few hours of the day.

(This definitely clarifies why being the parent of an infant was so horrific for me. There is no moment of the day when you are not totally responsible for an infant, and with my guilt already riding high, having an infant pushed me over the edge for a while, even with a superb co-parent along for the ride.)

Taking care of others’ needs is really tough for me. I do it lots, and I’m good at it. It has been a big part of my psyche from a very young age. But being good at it means it drains me. More specifically, I’m thinking as I type this, responsibility and guilt are very much blurred in my worldview. The difficult but intelligent Papusa Molina once said in a workshop on diversity, “Responsibility can be defined as the ability to respond.” Who can respond should. Who can’t need not feel guilty every moment of the day over it. But to what in this life can I not respond, with all my middle-class privilege (while others starve, suffer, die)?

How much money to charity is too much?

How many rescued pets is too many?

How often is leaving our son with a sitter too many?

How many visits to family instead of vacations is enough?

How many cookies are too many?

How often can you just let the phone ring and not answer it?

How often is often enough for taking the dog for a walk?

How long can you avoid housework without feeling like the Queen of Filth?

How much money do you give to friends whom you want to tell to “learn to budget”!

When will I stop feeling guilty that I had only one child?

How much work is enough, and when will I feel like “enough” IS enough?

The list goes on and on, and some days are better than others. Some days I don’t ask any of those questions at all. But most days I at least ask some. And, honestly, I think I differ from others not in how many questions I ask myself or how frequently I ask them (my guilt does usually come in leading question form, not in exclamation) but in how openly I admit (to myself and others) that I have such guilt.

“Just don’t worry about it” doesn’t work for me any more than for most of my friends and family. But some people are much better at blocking than others. And I know I annoy my friends most when what I say and do interferes with their blocking ability. When I confess to guilt, I bring up the subject for them. Sorry, friends, that’s just how it is. In fact, it's part of my best self, the one that analyzes and processes and works to make sense of things rather than just letting life flow by unquestioned. (Wow, not much guilt about being myself on that score apparently, hoorah!)

Actually, despite the sometimes crushing burden of guilt I take on, I do like myself. I do like my “ability to respond” and willingness to do so on many fronts. Perhaps this is a defensive strategy, praising myself for how much guilt I take on. But what else is our personality made up of apart from ways of seeing and ways of defending our ways of seeing? Coping strategies, blocking strategies—all kinds of strategies that spin around in our over-evolved heads. All that and blogging (don’t want to let too much time slip between posts or I’ll feel guilty about THAT!) keeps me a happy, busy (and busy-ness is next to godliness) human bean.

5.19.2006

Google Trends-iness

Mark Morford has inspired me again. Today’s column was on Google Trends, a handy service where you can look up which places in the world most often use Google to surf the Internet for certain terms (stats change daily). Morford discovers that Elmhurst, IL, for example, is the US city that most often looks up “anal sex” and “porn.”

Morford is wise in noting that this is more pseudo-information than truly useful fact. I definitely see the trend he sees in Elmhurst, but if I look up “feminist,” is it feminists or anti-feminists who are looking it up most? What do “global trends” mean when we have language issues (what is the equivalent word for “feminism” in Polish, Hindu, or Zulu)? Clearly, this tool has serious limitations. …But it’s addictive.

Here are some of the Googlicious factoids I discovered today:

Nowhere in the world do people look up the term “Christ” more frequently than in Nashville, TN, but it is Ashland City, TN and Lebanon, TN that top the list for looking up “Nashville.”

Delhi, India is the #1 city on the planet for looking up “namaste,” “masturbate,” and “hero.”

Halifax, Canada is off the charts on the term “empire,” with New York, London, and other US, UK, Canadian, and Australian cities trailing far behind.

Washington DC is champion for “feminist,” “genocide,” and “nuclear.”

The US is nowhere in the top ten for looking up either “Islam” or “clitoris.”

“War” is looked up much, much more often than “peace.”

...What can you learn today?

5.18.2006

ok ok......i give up.........you win..........CUTE ATTACK!!!

5.17.2006

Bifocal Bliss

I find out from Good Dr. Martin that I’m now a welcome member to the Over 40 Eyes Club, in that I am now officially farsighted. The previous/ongoing issue of problem with focus remains and is worse. I think my vision, which was

20/20 or better beforehand, got ruined by living in front of a Macintosh SE while writing my dissertation, back in the dot-matrix, pre-www days of 1990-1991. In any case, the prescription for the old glazzies is now higher, the distance vision is shot, and so...I must now embrace the wicked truth that, in one week when it’s time to pick up my fabulous new pair, I will be an Official Bifocal-wearing Old Fart.

20/20 or better beforehand, got ruined by living in front of a Macintosh SE while writing my dissertation, back in the dot-matrix, pre-www days of 1990-1991. In any case, the prescription for the old glazzies is now higher, the distance vision is shot, and so...I must now embrace the wicked truth that, in one week when it’s time to pick up my fabulous new pair, I will be an Official Bifocal-wearing Old Fart.The Doc did some laughing at my/our expense when I asked if I could have one pair of reading glasses and one pair of driving glasses. After all, I still don’t have to wear them all the time and they are for two separate purposes (hence the “bi” in “bifocal”). He said many people “in denial” do this until they just get over their vanity and acknowledge that this is just how things go when you hit your 40s. As your reading prescription gets strong enough to avoid the whanging headaches you’ve been denying have any relationship to your vision, it also means that when you look up from your book at your clock or your dog or your child smearing mashed potato on your clock or your dog that the world will be a fuzzy, blurry place. Now he did not say all of this, just the “denial” part. And he is, of course, absolutely right in my case.

Of course, as with all good pity parties, we must eventually stop the dance and take a moment to acknowledge that the cup may, indeed, be half full. I can still wear the glasses for reading and driving and keep them off other times. I made it 30 years with no glasses and another 10+ with weak ones. But the Bifocal Train is pullin’ into the station and I gotta ride it, however far from Youth Town it may be headed. Chugga chugga wooooooooo wooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo.

Trying to Blog About Breakfast on Pluto

In the end, I find myself wanting to read the novel that is so highly praised to see if perhaps my “It was good but not great” response to the film has something to do with the translation of novel to film. And I look forward to seeing more of Cillian Murphy’s work, ideally outside the superhero or other trite Americanized genres.

Meanwhile, I’ll read some more reviews and welcome feedback here about others’ experiences of the film.

5.05.2006

Trying to Do Deadwood

Given this interest and friends’ recommendations, I wanted to give Deadwood a try. Since it is on DVD, seeing the first season, episode by episode, seemed ideal. Because I don’t watch violence easily or lightly in most circumstances, I liked the idea of choosing when and how I’d watch it. And I like Ian McShane from his days in Lovejoy.

I’ve watched the first three episodes now, so I thought I’d weigh in on my response so far. First, this is typical genre stuff. The “Wild West” is as cartoonish as in good-old classic Hollywood westerns, and then you layer on HBO-style “gritty realism” (without ever dipping into actual “reality”). You get tons of swearing, hookers with gonorrhea, drug addiction, and a big death toll from living in a “real” squatter gold town beyond the reach of the U.S. government (Deadwood was, indeed, a real town similar to what is shown on the show—not to mention the name of a popular laid-back bar in Iowa City). You mix in some “real” famous people (Calamity Jane and Wild Bill Hickok) and dance around historical reports of their relationships while making a bunch of crap up as you go along to heighten tension.

Heightening tension gets at the heart of my current response to the series. There is so much tension, so much wondering who will get killed when and by whom, how dastardly will the next murder be…that it keeps my adrenalin flowing at what I can only call a toxic level. SO MUCH fight-or-flight response just isn’t good for my nervous system. Doesn’t matter whether I watch it at night (then have to find some way to come down for the next hour so I can go to sleep) or in the morning (then have to find some way to purge adrenalin that feels like a hit of speed or a dozen cups of coffee); in either case, I feel positively poisoned from riding the tension rollercoaster.

I know some people are addicted to this kind of a ride, and it definitely is a physiological experience as well as an emotional and marginally intellectual one. I’m guessing The Sopranos works similarly on people, as did NYPD Blue. I want to compare it to a literal rollercoaster ride, though for me it lacks the high.

It might help me if there were more character development in these first episodes. McShane’s Al Swearengen is about the best I’ve seen in episodes 1-3, especially if you like watching train wrecks. His depth of unethical, immoral, vicious behavior coupled with sociopathic calm in line delivery is engaging, in its villainous way. But watching him slap around prostitutes or order the murder of children gets exhausting, and predictable, fast.

And Calamity Jane better get more interesting – fast. Such an opportunity, and they have her cower before Swearengen without the (feminist) kindness of having him trigger memories of abuse as a child or some credible reason to bring down this calamitous cross-dresser. Her relationship with Hickok, however unrequited, has great genderbending implications, but so far the show is making her more the butt of jokes than a truly compelling character. She doesn’t have to be Xena, but she should be compelling. But hell, so should Hickok. Not to mention Seth Bullock, the dullest character this side of any western (does he have the ability to look at someone in a way other than up at an angle from beneath his hat/brow, or has someone told the director this is “sexy”?). And Sol Star (oy vey that name) is our token Jew (ho hum).

I do get that Deadwood is a show about westerns even more than it is a western. It’s a postmodern western. It’s a metawestern. But then, not really. I think my biggest criticism is that it isn’t fully in the genre and it isn’t fully outside the genre. Some will say this is its brilliance. But until it has some characters that truly grip me, it’s a long hour. Just pass me some of Alma’s laudanum so I can come down more quickly after the adrenalin poisoning and I’ll try to make it a few more episodes before I move on to something else.

4.22.2006

The Cultural Politics of the CAT Scan Experience

Anyhow, the point of this unpleasant blog is how unpleasant the damn CAT scan was! The real rant, though (given the general aims of this blog), is less to bitch about the procedure than to bitch about the way the procedure is and is not represented to the patient. Here is a list of my complaints:

1. The doctor made it seem entirely simple and without complication or discomfort. He did give the usual caveat, glibly babbled off, about people dying from the procedure in very rare cases, to which I replied, “How can you say I have nothing to worry about AND that I might die from it?” “Don’t worry, we’ll take good care of you,” he smiled into my face. And off I went to schedule it.

2. The nurse in the X-ray area gave me two bottles of yuck to drink without ever once mentioning—verbally or on the instruction sheet—that this barium stuff causes bloating, cramping, serious gas, and even diarrhea. She did say it has a metallic taste and to put it in the fridge before drinking it. (The flavor was mildly coconut, but the texture was something between school glue and male ejaculate—ok, that’s DEFINITELY more than you wanted to read, but it gets across the point of how difficult it was to guzzle down in quantity.) She did not, however, say “Watch out for the runs!” (The CAT scan technician put it this way when I complained of the cramping during the procedure: “Oh, some people don’t even get diarrhea.”) In that waiting room after swigging the shit down, I made several potty trips in half and hour and passed so much gas I could’ve filled a hot-air balloon.

3. The “contrast dye” they use for your organs is, as the doctor said, “an injection,” but he didn’t say it was through an IV! Those things HURT and the dye can cause hives, shortness of breath, or more severe allergic reaction, including death. No one told me this until I was already in the CAT scan room with the Donut of Doom looming before me. The technician did tell me that the dye would give me a burning sensation in my throat and bladder, and it did, but it passed quickly.

4. Oh yeah, they make you injest ANOTHER large cup of barium yuck (this time it wasn’t coconut glue but metallic orange fizz) just before you lie down, to “top you off” as the technician said.

5. The actual renal/pelvic CAT scan requires that you hold your breath about 10 times during the procedure, between 10 and 30 seconds each. This isn’t tough unless you’re already hyperventilating, of course, which I’m happy to say I wasn’t. However, it is not easy to hold your breath over and over again when you’re having increasingly sharp gas pains from being overfull of barium yuck and having to lie prone with it gurgling through your guts.

In the end, I lived to tell the tale. I withstood the horrid IV experience, held my breath as required between stabbing gas pains, passed the barium yuck over the course of the day from every orifice, and then went shopping (found a remarkable pink tank top with Tank Girl on it, saying “Oh, the preposterous bollocks of the situation!” at Marshalls—an unexpected treasure).

What I want is for doctors and nurses to let people know this stuff awaits them with this “simple procedure.” Just a little sheet saying that some of this may happen to them. But truly informed consent seems something the medical community is just simply uninterested in.

4.18.2006

Riddle

4.02.2006

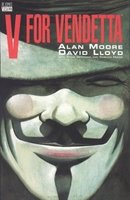

Yes, I Enjoyed V for Vendetta

I was disturbed to hear that V for Vendetta cost $54 million. (Worldwide it’s already earned $70 million, so all is right with the world, eh?) Now, I’m always frustrated by how much a few hours escape at the cinema costs, even when a film is life-changing (this one isn’t). (Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, which was life-changing for me, cost $6.5 million, by contrast. And Brokeback only cost $14 million.) During the film, I’m generally in filmgoer space, mentally, but before and after I often think about those abstract “liberal” ideas like “feed all homeless people for a year or make one movie…hmmmm….”

But if we surrender to the wisdom that says “it doesn’t work like that” and just look at the film, what do we have? First, we have to consider the issue of the Wachowski brothers label on the film. Yes, they are able to tap into cultural anxieties and do a good job of rendering comic books (literally and metaphorically) in the (cinematic) flesh. The Matrix, like V for Vendetta, captivated through focus on a world beyond our control—one via extra-terrestrial domination and one via political repression. Each film gripped and entertained me, got me thinking about how much we take for granted and also how much life resembled the film world. (Come to think of it, I liked Dark City this way, too.) Yet, The Matrix had more in common with the first Alien film

(and the sequels yielded horror to sci-fi for both series—though the second Matrix film was no Aliens). By contrast, V for Vendetta, from a graphic novel I liked less than Watchmen but enjoyed, has more in common with 1984 (and I did like seeing John Hurt go from a long-ago turn as Winston Smith to another incarnation of Big Brother in V for Vendetta). Given that the Wach Bros. didn’t write or direct the thing, my criticism of them centers primarily on the ghastly budget and a curiosity of how much of that budget was truly needed to make the film.

(and the sequels yielded horror to sci-fi for both series—though the second Matrix film was no Aliens). By contrast, V for Vendetta, from a graphic novel I liked less than Watchmen but enjoyed, has more in common with 1984 (and I did like seeing John Hurt go from a long-ago turn as Winston Smith to another incarnation of Big Brother in V for Vendetta). Given that the Wach Bros. didn’t write or direct the thing, my criticism of them centers primarily on the ghastly budget and a curiosity of how much of that budget was truly needed to make the film.With that out of the way, I want to praise the content and political pleasure I had in the film. I absolutely loved the heavy-handed Bush slams in the film. From a graphic novel aimed at Thatcher to this obvious and downright gleeful attack on Dubya, Cheney, Rumsfeld, and the rest of the gang of lying, dangerous thugs; V for Vendetta is a wonderful reminder that many of us can see that the emperor has no clothes, that Empires must fall, and that intelligence and art will triumph over greed and power-mongering (thank you, Cyrano). It was uplifting, dammit. Like watching The Daily Show, I need some good Leftist uplift in my media, however hammer-you-over-the-head simple in metaphors and symbols it may be.

Does this mean that Natalie Portman’s shaved head bit doesn’t rely on Holocaust imagery it does not earn (can’t help but compare her negatively to Hurt in 1984, where the metaphor was far better earned and not played for titillation)? Naah. (And omigod, look at that picture! Found it on a random search. “Prison torture can make me feel soooooooooo sexy!”)

Does this mean that Natalie Portman’s shaved head bit doesn’t rely on Holocaust imagery it does not earn (can’t help but compare her negatively to Hurt in 1984, where the metaphor was far better earned and not played for titillation)? Naah. (And omigod, look at that picture! Found it on a random search. “Prison torture can make me feel soooooooooo sexy!”) But go see the film. I did truly enjoy it.

3.21.2006

A Little Lenny Bruce

He celebrates the importance of the First Amendment and ridicules our use of it. We can deny others’ gods, say “A fat slob, the Buddha” or “go in front of a synagogue and sing about pork.” We can disrespect any group we want, “Cause that’s our right—to be disgusting.” After all, “[T]he reason we left England was just for that right, to be disgusting.”

But obscenity is about arousing the “prurient interest,” about turning people on. And, Lenny says, “The prurient interest is like the steel interest. What’s wrong with appealing to the prurient interest? We appeal to the killing interest.” And, more, he notes the classism here. If I write about trailer trash having vivid, graphic, sloppy sex, then that’s obscene. But if I’m “classy” about it, if I know how to “handle” the sex scenes with artistic beauty (he talks about Lady Chatterly's Lover as an example), if it emerges as “legit” art, then I’m far less likely to be prosecuted. In Lenny’s words, “So, in the opinion of this court, we punish untalented artists.”

3.18.2006

You and Me and ADD Makes Three

First, in diagnosing ADD via the DSM (huge encyclopedia of psychological disorders put out by the American Psychiatric Association – aka doctors not psychologists), the criteria are so broad (everything from lack of ability to concentrate to disliking work tasks) and the determining degree so vague (one has to display only “some” of the characteristics “some” of the time), that every single kindergartener in this country could be aptly diagnosed with ADD. Add to this the fact that many medical doctors with no psychological training are diagnosing the disorder and prescribing Ritalin and you have, in my opinion, a recipe for self-made epidemic.

My conclusion has caused me conflict, to be sure. For example, Chad and I have dear friends who assert that both father and son have ADD and the son is now on Ritalin and they are seeing a marked improvement in his ability to concentrate and succeed in school. I do not doubt their results nor their frustration with their son’s past behavior and difficulties. Who am I to second-guess what they need to do for their family?

Yet, I do have concerns. Chad has cited studies that show that therapy works for this type of disorder/situation. We both have more faith in therapists/counselors than medical doctors. And now I’ve found a way of seeing ADD that reduces my conflicts and eases my mind. As Morford puts it, we are an ADD culture.

With the demands for and pleasures of constant multitasking (like right now I’m on yahoo messenger chatting with a friend, talking now and then to my son about a videogame he’s playing with his dad, writing this blog entry, and finishing breakfast), ADD is a treasured commodity. An ability to concentrate on one thing too long would be excessive, a waste of valuable time that might always be stuffed far more full if we just try a little harder. I remember an NPR editorial a few years back that talked about our being a culture more invested in seeming busy than in actually doing work (or doing pleasure). His ultimate example was people on cell phones in public bathrooms, wanting others to hear them as they make important business decisions while they piss. From the critical vantage point of this moment, the commentator’s description is positively naïve. Everybody not only has a cell phone and uses it constantly, but increasingly few people aren’t willing to talk while on the pot.

If we are, indeed, an ADD-inspiring culture, then when numerous adults and their numerous children tell me they have ADD, I have a new lens through which to see it that keeps me from being at odds with their definitions and even their cures. After all, as Joshua Foer in “The Adderall Me: my romance with ADD meds” makes plain, ADD drugs can help everyone to better deal with a culture that increasingly insists on ADD personalities to meet the needs of our ADD culture.

If we are, indeed, an ADD-inspiring culture, then when numerous adults and their numerous children tell me they have ADD, I have a new lens through which to see it that keeps me from being at odds with their definitions and even their cures. After all, as Joshua Foer in “The Adderall Me: my romance with ADD meds” makes plain, ADD drugs can help everyone to better deal with a culture that increasingly insists on ADD personalities to meet the needs of our ADD culture.Nothing like a political/sociological perspective to shed light on the medical/psychological, eh?

3.17.2006

3.12.2006

Religion, Science--the Whole Megillah

Discussions of “Creationism,” that frightening pseudo-concept that reminds one of Stephen Colbert’s “truthiness” more than of a logical and meaningful combination of religion and science are more disturbing than I can say as a college professor. It seems clear to the point of inarguable to me that what science intends and how science works is incompatible with the concept of religion. Religion and science are, in intent and usage, often simply antithetical.

Take the scientific method: a systematic pursuit of knowledge involving the formulation of a question or problem, collection of data through observation and experiment, and the formulation and testing of hypotheses. Religion is simply not interested in data collection, experiment, and testing, except metaphorically or philosophically (and not even that if we’re talking fundamentalism). Religion is about taking things on faith. So, we plain and simply cannot bring religion into the science classroom. It just won’t fit through the damn door.

This said, science should not be taken for/as religion. There are questions science is entirely uninterested in, ill-suited for, or just plain incapable of addressing. Chemistry lab can’t help me answer “Do human beings have a soul?”, nor need it do so. If science becomes the only valuable way of knowing, we place equally artificial limits on ways of seeing and being in the world. There are questions of personal and cultural values that science cannot adequately address for me. But then, organized religion often cannot either.

In a recent issue of Reform Judaism, I read an article entitled “Evolution and Eden: Why Darwinism and Judaism are Perfectly Compatible” (Spring 2006: 44-46, 48). The Encino, CA rabbi who wrote the article, Harold M. Schulweis, may go places I do not because I am a secular Jew, but he offers some discussion of the Torah (the first five books of the Hebrew Bible or “Old Testament”) that I wish other well-meaning people of faith would grasp.

Schulweis asks, “What rescued Judaism from a rigid, fundamentalist literalism?” and answers that the Torah “possesses the essential character of poetry, not literal prose. To comprehend Torah you have to understand symbols, parables, metaphors, and allegories. Torah is art, a spiritual interpretation of life, not a mechanical record of facts—more like a love sonnet than a legal contract.”

I remember to this day a course at the University of Iowa taught by the amazing Rabbi Jay Holstein. His Old Testament Survey courses were among the most popular at the university when I attended graduate school there. The story of Cain and Abel as he tells it is illustrative. Let's take just a moment of it, stylized in my own fashion:

Q: If the name Cain is based on the Hebrew verb “to buy” and Abel means “vapor,” what are the odds this story is more important at a literal level (a tale of the children of the first humans) than as parable (what happens when you try to buy God’s favor)?

A: Who the heck names their son “vapor” and expects him to stick around, for pity’s sake?!

Frankly, I don’t engage much with religion in my life because religion is too slippery, too ripe for self-fulfilling prophesy and bandwagon craziness. The beautiful “poetry” of the Bible, for example, is in too many minds and hands a tool to interpret with personal bias then beat people over the head with. If I agree with Rabbi Schulweis that “Science is concerned with facts. The Torah is concerned with values,” I may not agree with him on defining and/or applying those Biblical “values.” If “Science is concerned with ‘what is’” and “The Torah is concerned with ‘what ought to be,’” then I’m very nervous about who gets to decide “what ought to be” and how these “morally driven” religious folk come to their conclusions.

What Schulweis does not distinguish is as important as what he does. We are allies in not wanting religion in the science classroom, but I do not believe you need religion to address the fact that “because science is morally neutral it is morally malleable; it can be made to justify healing or greed, selflessness or selfishness.” Everything is political, nothing is “morally neutral”—especially not the way it is practiced. A textbook definition of the scientific method may be “morally neutral,” but this method has been developed by “moral” beings within specific historical, political, and social contexts. It cannot be free of that stain, nor can any way of doing or being.

Certainly, I am thrilled to know that “[r]are is a rabbi” who would argue that “permitting the use of federal funds for medical research with stem cells taken from human embryos […] runs counter to God’s will,” yet I do not know that “[s]cience needs the conscience of Torah.” Science needs conscience, Torah needs conscience, “all God’s children” need conscience. But who decides the contours of that conscience, who decides how, when, where, and why to apply conscience? That kind of question I don’t want (interpretation of) Torah, the New Testament, the Koran, or any religious text to dictate, in or out of the classroom.